Amersfoort

Amersfoort | |

|---|---|

City and municipality | |

| Images, from top down, left to right: Zuidsingel, Havik, Lieve Vrouwekerkhof and Woudzoom | |

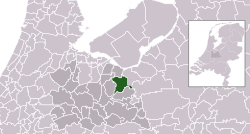

Location in Utrecht | |

| Coordinates: 52°9′N 5°23′E / 52.150°N 5.383°ECoordinates: 52°9′N 5°23′E / 52.150°N 5.383°E | |

| Country | Netherlands |

| Province | |

| City rights | 1259 |

| Government | |

| • Body | Municipal council |

| • Mayor | Lucas Bolsius (CDA) |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 63.86 km2 (24.66 sq mi) |

| • Land | 62.86 km2 (24.27 sq mi) |

| • Water | 1.00 km2 (0.39 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 3 m (10 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Municipality | 156,286 |

| • Density | 2,486/km2 (6,440/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 180,539 |

| • Metro | 287,110 |

| Demonym(s) | Amersfoorter(s) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postcode | 3800–3829 |

| Area code | 033 |

| Website | www |

Amersfoort [ˈaːmərsfoːrt] (![]() listen) is a city and municipality in the province of Utrecht, Netherlands and is situated at the eastern edge of the Randstad. As of January 1st 2019, the municipality had a population of 156,286, making it the second-largest of the province and fifteenth-largest of the country. Amersfoort is also one of the largest Dutch railway junctions with its three stations—Amersfoort Centraal, Schothorst and Vathorst—due to its location on two of the Netherlands' main east to west and north to south railway lines. The city was used during the 1928 Summer Olympics as a venue for the modern pentathlon events. Amersfoort marked its 750th anniversary as a city in 2009.[6]

listen) is a city and municipality in the province of Utrecht, Netherlands and is situated at the eastern edge of the Randstad. As of January 1st 2019, the municipality had a population of 156,286, making it the second-largest of the province and fifteenth-largest of the country. Amersfoort is also one of the largest Dutch railway junctions with its three stations—Amersfoort Centraal, Schothorst and Vathorst—due to its location on two of the Netherlands' main east to west and north to south railway lines. The city was used during the 1928 Summer Olympics as a venue for the modern pentathlon events. Amersfoort marked its 750th anniversary as a city in 2009.[6]

Contents

Population centres[edit]

The municipality of Amersfoort consists of the following cities, towns, villages and districts: Bergkwartier, Bosgebied, Binnenstad, Hoogland, Hoogland-West, Kattenbroek, Kruiskamp, de Koppel, Liendert, Rustenburg, Nieuwland, Randenbroek, Schuilenburg, Schothorst, Soesterkwartier, Vathorst, Hooglanderveen, Vermeerkwartier, Leusderkwartier, Zielhorst and Stoutenburg-Noord.

History[edit]

Hunter gatherers set up camps in the Amersfoort region in the Mesolithic period. Archaeologists have found traces of these camps, such as the remains of hearths, and sometimes microlithic flint objects, to the north of the city.

Early years[edit]

Remains of settlements in the Amersfoort area from around 1000 BC have been found, but the name Amersfoort, after a ford in the Amer River, today called the Eem, did not appear until the 11th century. The city grew around what is now known as the central square, the Hof, where the Bishops of Utrecht established a court in order to control the "Gelderse Vallei" area. It was granted city rights in 1259 by the bishop of Utrecht, Henry I van Vianden. A first defensive wall, made out of brick, was finished around 1300. Soon after, the need for enlargement of the city became apparent and around 1380 the construction of a new wall was begun and completed around 1450. The famous Koppelpoort, a combined land and water gate, is part of this second wall. The first wall was demolished and houses were built in its place. Today's Muurhuizen (wallhouses) Street is at the exact location of the first wall; the fronts of the houses are built on top of the first city wall's foundations.

The Onze-Lieve-Vrouwentoren (Tower of Our Lady)[7] is one of the tallest medieval church towers in the Netherlands at 98 metres (322 ft). When it was built, it was the middle point of The Netherlands[8], it was exactly built in the center and a reference for the Dutch grid system. The nickname of the tower is Lange Jan ('Long John'). [9]

The construction of the tower and the church was started in 1444. The church was destroyed by an explosion in 1787, but the tower survived, and the layout of the church still can be discerned today through the use of different types of stone in the pavement of the open space that was created. It is now the reference point of the RD coordinate system, the coordinate grid used by the Dutch topographical service: the RD coordinates are (155.000, 463.000).

The inner city of Amersfoort has been preserved well since the Middle Ages. Apart from the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwetoren, the Koppelpoort, and the Muurhuizen (Wall-houses), there is also the Sint-Joriskerk (Saint George's church), the canal-system with its bridges, as well as medieval and other old buildings; many are designated as national monuments. In the Middle Ages, Amersfoort was an important centre for the textile industry, and there were a large number of breweries. Jews also lived in Amersfoort in the Middle Ages, before being expelled from the province in 1546 and beginning to return to the city in 1655.[10]

Origin of the Keistad[edit]

The nickname for Amersfoort, Keistad (boulder-city), originates in the Amersfoortse Kei, a 9-tonne (19,842 lb) boulder that was dragged from the Soest moors into the city in 1661 by 400 people because of a bet between two landowners. The people got their reward when the winner bought everyone beer and pretzels. Other nearby towns then nicknamed the people of Amersfoort Keientrekker (boulder-puller). This story embarrassed the inhabitants, and they buried the boulder in the city in 1672, but after it was found again in 1903 it was placed in a prominent spot as a monument. There are not many boulders in the Netherlands, so it can be regarded as an icon.

Nieuw Amersfoort[edit]

One of the six Dutch towns established in the 17th Century in what is now Brooklyn was called "Nieuw Amersfoort" (New Amersfoort). The original patentees were Wolfert Gerritse van Kouwenhoven and Andries Hudde.[11] Unlike other Dutch names which were retained up to the present, Nieuw Amersfoort is now called "Flatlands".

In the 18th century the city flourished because of the cultivation of tobacco,[note 1] but from about 1800 onwards began to decline.

The decline was halted by the establishment of the first railway connection in 1863, and, some years later, by the building of a substantial number of infantry and cavalry barracks, which were needed to defend the western cities of the Netherlands.

After the 1920s growth stalled again, until in 1970 the national government designated Amersfoort, then numbering some 70,000 inhabitants, as a "growth city".

Second World War[edit]

Since Amersfoort was the largest garrison town in the Netherlands before the outbreak of the Second World War, with eight barracks, and part of the main line of defence, the whole population of then 43,000 was evacuated at the start of the invasion by the Germans in May 1940. After four days of battle, the population was allowed to return.

There was a functioning Jewish community in the town, at the beginning of the war numbering about 700 people. Half of them were deported and killed, mainly in Auschwitz and Sobibor. In 1943, the synagogue, dating from 1727, was severely damaged on the orders of the then Nazi-controlled city government. It was restored and opened again after the war, and has been served since by a succession of rabbis.

There was a Nazi concentration camp near the city of Amersfoort during the war. The camp, officially called Polizeiliches Durchgangslager Amersfoort (Police Transit Camp Amersfoort), better known as Kamp Amersfoort, was actually located in the neighbouring municipality of Leusden.

After the war the leader of the camp, Joseph Kotälla, served a life sentence in prison. He died in captivity in 1979. Some of the victims of the camp are buried in Rusthof cemetery near the town.

Among the victims were prisoners of war from the Soviet Union, including 101 Central Asians, mostly Uzbeks or citizens of Samarqand. Locals would commemorate them, but the identity of the 101 soldiers was not known, until journalist Remco Reiding started investigating this case in 1999, after hearing about the cemetery. Amongst the few remaining people who witnessed the 101 soldiers is Henk Broekhuizen.[12][13]

Culture[edit]

Museums[edit]

- The Mondriaan House: birthplace of the painter Piet Mondriaan. Exhibits a lifesize reconstruction of his workshop in Paris. Some temporary shows and work by artists inspired by the painter.

- Flehite: historic, educational and temporary exhibitions behind a splendid facade. The museum closed in 2007 due to asbestos contamination. It was refurbished and reopened in May 2009.

- Zonnehof: small elegant modernist building designed by Gerrit Rietveld on an eponymous square just south of the centre with temporary exhibitions of mostly contemporary art.(closed)

- Armando Museum: work by the painter Armando who lived in Amersfoort as a child in a renovated church building. Most of the church and the art on exhibition was destroyed in a fire on 22 October 2007.[14]

- Dutch Cavalry Museum: museum in 475 years old barracks. Most other military museums in the Netherlands got absorbed into the National Military Museum (Nationaal Militair Museum), but the cavalry museum has stood strong. It shows Dutch cavalry and tanks.

- Culinary Museum (was closed in 2006).

- Kunsthal KAdE:[15] a modern art exhibition hall.

Sports[edit]

Amersfoort had its own professional football (soccer) club named HVC Amersfoort. It was founded on 30 July 1973, but disbanded on 30 June 1982 because of financial problems. The city also hosted the riding part of the modern pentathlon event for the 1928 Summer Olympics.[16] Amersfoort also hosted the Dutch Open (tennis) tournament from 2002 till its end in 2008.

Other[edit]

The city has a zoo, DierenPark Amersfoort, which was founded in 1948. Amersfoort is the greenest city in the Netherlands.

Transport[edit]

Bus[edit]

Bus services are provided by 2 firms: U-OV and Syntus. Syntus provides services in town and the entirety of the province Utrecht, save for the bus to the city Utrecht, which is provided by U-OV.

Rail[edit]

Amersfoort has three railway stations:

- Amersfoort Centraal, the main station, located on the western edge of the city at the crossing of the Amsterdam–Zutphen and Utrecht–Kampen railways

- Amersfoort Schothorst, located northeast of the city centre on the Utrecht–Kampen railway

- Amersfoort Vathorst, located in the extreme northeast of the city on the Utrecht–Kampen railway

All three serve direct trains to Utrecht Centraal and Zwolle. Amersfoort Centraal and Amersfoort Schothorst also have direct service to Den Haag Centraal, Amsterdam Centraal, and Amsterdam Zuid. Amersfoort Centraal further serves direct trains to Enschede, Rotterdam Centraal, Schiphol Airport, Leeuwarden, Groningen, Ede–Wageningen and Berlin Hauptbahnhof.

Road[edit]

Two major motorways pass Amersfoort:

- along the north, the A1 motorway (Amsterdam–Apeldoorn)

- along the east, the A28 motorway (Utrecht–Groningen)

Water[edit]

The river Eem (pronounced roughly "aim") begins in Amersfoort, and the town has a port for inland water transport. The Eem connects to the nearby Eemmeer (Lake Eem). The Valleikanaal drains the eastern Gelderse Vallei and joins with other sources to form the Eem in Amersfoort.

Local government[edit]

The municipal council of Amersfoort consists of 39 seats, which are divided as follows:[17][18]

- GroenLinks – 6 seats (3 seats in 2014)

- VVD – 6 seats (5 seats in 2014)

- D'66 – 6 seats (9 seats in 2014)

- CDA – 6 seats (4 seats in 2014)

- ChristenUnie – 4 seats (5 seats in 2014)

- Amersfoort2014 – 3 seat (1 in 2014)

- SP – 3 seats (4 seats in 2014)

- Burger Partij Amersfoort – 2 seats (2 seats in 2014)

- PvdA – 2 seats (5 seats in 2014)

- Denk – 1 seat (not represented in 2014)

The city has a court of first instance (kantongerecht) and a regional chamber of commerce.

Economy[edit]

The city is a main location for several international companies:

- Royal VolkerWessels Stevin N.V., a major European construction-services business.

- FrieslandCampina, a Dutch dairy cooperative.

- Royal HaskoningDHV, consultants and engineers.

- Golden Tulip Hospitality Group, international hotel chain Golden Tulip Hotels, Inns and Resorts.[19]

- Nutreco, animal feed and human foodstuffs

- Yokogawa Electric, an electrical engineering and software company, the European headquarters for which are located in Amersfoort

It also has a number of non-governmental organizations and foundations:

- Christian Union, a Christian democratic political party in the Netherlands.

- Oikocredit, headquarters of global cooperative society, financing economic development focused on poverty alleviation.

- Socialist Party, a left-wing social-democratic political party in The Netherlands.

- KNLTB, the Dutch national lawn-tennis association.

- Vereniging Eigen Huis, the largest home-owners association in the Netherlands; with 700,000 members, it is also the largest in the world

Notable residents[edit]

- Paulus Buys (1531–1594) – Grand Pensionary

- Johan van Oldenbarnevelt (1547–1619) – statesman

- Piet Mondriaan (1872–1944) – painter, pioneer of 20th century abstract art

- Willem Sandberg (1897–1984) – graphic designer, Stedelijk Museum director

- Jan van Hulst (1903-1975) – recognised as Righteous Among the Nations

- Johannes Heesters (1903–2011) – actor and singer [20]

- Victor Kaisiepo (1948–2010) – advocate for West Papuan self-determination.[21]

- Paul Cobben (born 1951) – philosopher

- Gino Vannelli (born 1952) – Canadian singer, songwriter, musician and composer

- Father Roderick Vonhögen (born 1968) – television host and podcaster

- Blaudzun (born 1974) – singer and filmmaker, stage name of Johannes Sigmond[22]

- Sarah Wiedenheft (1993) – anime dubbing actress [23]

- Sport

- Ben Pon (senior) (1904–1968) – car importer and developer of the Volkswagen Type 2

- Ben Pon (born 1936-2019) – sports car racing driver

- Loet Geutjes (born 1943) – water polo player

- Feike de Vries (born 1943) – water polo player

- Ton van Heugten (1945–2008) – former sidecarcross world champion

- Anke Rijnders (born 1956) – swimmer

- Frank Drost (born 1963) – swimmer

- Joop Kasteel (born 1964) – Professional Fighter and Bodybuilder

- Jan Wagenaar (born 1965) – water polo player

- John van den Brom (born 1966) – a former professional footballer and manager

- Arie van de Bunt (born 1969) – water polo goalkeeper

- Valentijn Overeem (born 1976) – mixed martial artist

- Alistair Overeem (born 1980) – mixed martial artist & kickboxer

- Marco van Ginkel (born 1992) – Dutch football player for Milan & the Netherlands national team

Sister city[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Burgemeester" [Mayor] (in Dutch). Gemeente Amersfoort. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ "Kerncijfers wijken en buurten" [Key figures for neighbourhoods]. CBS Statline (in Dutch). CBS. 2 July 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ^ "Postcodetool for 3811LM". Actueel Hoogtebestand Nederland (in Dutch). Het Waterschapshuis. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ "Bevolkingsontwikkeling; regio per maand" [Population growth; regions per month]. CBS Statline (in Dutch). CBS. 1 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ "Bevolkingsontwikkeling; regio per maand" [Population growth; regions per month]. CBS Statline (in Dutch). CBS. 26 June 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ^ "Home Page" (in Dutch). Amersfoort 750. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- ^ "Onze Lieve Vrouwentoren". SkyscraperCity. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- ^ "Wat te doen in Amersfoort?". Roëlle.

- ^ "Amersfoort - Middle point of the Netherlands". OnzeLieveVrouwenToren.

- ^ "The Jewish Community of Amersfoort". The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

- ^ Kilgannon, Corey (1 November 2007). "Dutch Deed Fetches More Than a Handful of Beads". City Room. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ "Soviet Field of Glory" (in Russian)

- ^ Rustam Qobil (9 May 2017). "Why were 101 Uzbeks killed in the Netherlands in 1942?". BBC. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ "Armando Museum fire". Armandomuseum.nl. 22 October 2007. Archived from the original on 11 November 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- ^ Kunsthalkade.nl

- ^ van Rossem, George, ed. (1931). The ninth Olympiad, being the official report of the Olympic games of 1928 celebrated at Amsterdam (PDF). Translated by Sydney W. Fleming. Amsterdam: Netherlands Olympic Committee (Committee 1928); J.H. de Bussy. p. 277. OCLC 10243706. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2008.

- ^ "Leden Gemeenteraad" (in Dutch). Gemeente Amersfoort. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ "Verkiezingsuitslag(stemaantalen en zetelverdeling 3 maart 2010" (in Dutch). Gemeente Amersfoort. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ "Contact". Golden Tulip Hospitality Group. Archived from the original on 12 September 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ IMDb Database retrieved 11 November 2019

- ^ "Papuan activist Kaisiëpo dies". Radio Netherlands Worldwide. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- ^ "Blaudzun" (in Dutch). Muziek Encyclopedie. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ IMDb Database retrieved 11 November 2019

Notes[edit]

- ^ The Russian word for the tobacco Nicotiana rustica, махорка (makhorka), may bear an etymological debt to this city. See the dictionary of Max Vasmer.

External links[edit]

Media related to Amersfoort at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Amersfoort at Wikimedia Commons Amersfoort travel guide from Wikivoyage

Amersfoort travel guide from Wikivoyage- Official website

No comments:

Post a Comment