Chartism

Chartism was a working-class male suffrage movement for political reform in Britain that existed from 1838 to 1857. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, with particular strongholds of support in Northern England, the East Midlands, the Staffordshire Potteries, the Black Country, and the South Wales Valleys. Support for the movement was at its highest in 1839, 1842, and 1848, when petitions signed by millions of working people were presented to the House of Commons. The strategy employed was to use the scale of support which these petitions and the accompanying mass meetings demonstrated to put pressure on politicians to concede manhood suffrage. Chartism thus relied on constitutional methods to secure its aims, though there were some who became involved in insurrectionary activities, notably in South Wales and in Yorkshire.

The People's Charter called for six reforms to make the political system more democratic:

- A vote for every man twenty-one years of age, of sound mind, and not undergoing punishment for a crime.

- The secret ballot to protect the elector in the exercise of his vote.

- No property qualification for Members of Parliament in order to allow the constituencies to return the man of their choice.

- Payment of Members, enabling tradesmen, working men, or other persons of modest means to leave or interrupt their livelihood to attend to the interests of the nation.

- Equal constituencies, securing the same amount of representation for the same number of electors, instead of allowing less populous constituencies to have as much or more weight than larger ones.

- Annual Parliamentary elections, thus presenting the most effectual check to bribery and intimidation, since no purse could buy a constituency under a system of universal manhood suffrage in each twelve-month period.

Chartists saw themselves fighting against political corruption and for democracy in an industrial society, but attracted support beyond the radical political groups for economic reasons, such as opposing wage cuts and unemployment.[1][2]

Contents

Origin[edit]

After the passing of the Reform Act 1832, which failed to extend the vote beyond those owning property, the political leaders of the working class made speeches claiming that there had been a great act of betrayal. This sense that the working class had been betrayed by the middle class was strengthened by the actions of the Whig governments of the 1830s. Notably, the hated new Poor Law Amendment was passed in 1834, depriving working people of outdoor relief and driving the poor into workhouses, where families were separated. It was the massive wave of opposition to this measure in the north of England in the late 1830s that gave Chartism the numbers that made it a mass movement. It seemed that only securing the vote for working men would change things, and indeed Dorothy Thompson, the preeminent historian of Chartism, defines the movement as the time when "thousands of working people considered that their problems could be solved by the political organization of the country."[3]:1 In 1836 the London Working Men's Association was founded by William Lovett and Henry Hetherington,[4] providing a platform for Chartists in the southeast. The origins of Chartism in Wales can be traced to the foundation in the autumn of 1836 of Carmarthen Working Men's Association.[5]

Press[edit]

Both nationally and locally a Chartist press thrived in the form of periodicals, which were important to the movement for their news, editorials, poetry and (especially in 1848) reports on international developments. They reached a huge audience.[6] The Poor Man's Guardian in the 1830s, edited by Henry Hetherington, dealt with questions of class solidarity, manhood suffrage, property, and temperance, and condemned the Reform Act of 1832. The paper explored the rhetoric of violence versus nonviolence, or what its writers called moral versus physical force.[7] It was succeeded as the voice of radicalism by an even more famous paper: the Northern Star and Leeds General Advertiser. The Star was published between 1837 and 1852, and in 1839 was the best-selling provincial newspaper in Britain, with a circulation of 50,000. Like other Chartist papers it was often read aloud in coffeehouses, workplaces and the open air.[8] Other Chartist periodicals included the Northern Liberator (1837–40), English Chartist Circular (1841–3), and the Midland Counties' Illuminator (1841). The papers gave justifications for the demands of the People's Charter, accounts of local meetings, commentaries on education and temperance and a great deal of poetry. They also advertised upcoming meetings, typically organised by local grassroots branches, held either in public houses or in their own halls.[9] Research of the distribution of Chartist meetings in London that were advertised in the Norther Star shows that the movement was not uniformly spread across the metropolis but clustered in the West End, where a group of Chartist tailors had shops, as well as in Shoreditch in the east, and relied heavily on pubs that also supported local friendly societies.[10] Readers also found denunciations of imperialism—the First Opium War (1839–42) was condemned—and of the arguments of free traders about the civilizing and pacifying influences of free trade.[11]

People's Charter of 1838[edit]

In 1837, six Members of Parliament and six working men, including William Lovett (from the London Working Men's Association, set up in 1836) formed a committee, which in 1838 published the People's Charter. This set out the movement's six main aims.[12] The achievement of these aims would give working men a say in lawmaking: they would be able to vote, their vote would be protected by a secret ballot, and they would be able to stand for election to the House of Commons as a result of the removal of property qualifications and the introduction of payment for MPs. None of these demands were new, but the People's Charter became one of the most famous political manifestos of 19th-century Britain.[13]

Beginnings[edit]

Chartism was launched in 1838 by a series of large-scale meetings in Birmingham, Glasgow and the north of England. A huge mass meeting was held on Kersal Moor near Salford, Lancashire, on 24 September 1838 with speakers from all over the country. Speaking in favour of manhood suffrage, Joseph Rayner Stephens declared that Chartism was a "knife and fork, a bread and cheese question".[14] These words indicate the importance of economic factors in the launch of Chartism. If, as the movement came together, there were different priorities amongst local leaders, the Charter and the Star soon created a national, and largely united, campaign of national protest. John Bates, an activist, recalled:

There were [radical] associations all over the county, but there was a great lack of cohesion. One wanted the ballot, another manhood suffrage and so on ... The radicals were without unity of aim and method, and there was but little hope of accomplishing anything. When, however, the People's Charter was drawn up ... clearly defining the urgent demands of the working class, we felt we had a real bond of union; and so transformed our Radical Association into local Chartist centres ...[3]:60

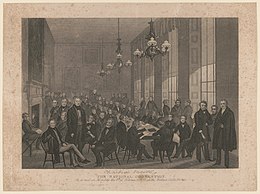

The movement organised a National Convention in London in early 1839 to facilitate the presentation of the first petition. Delegates used the term MC, Member of Convention, to identify themselves; the convention undoubtedly saw itself as an alternative parliament.[15]:19 In June 1839, the petition, signed by 1.3 million working people, was presented to the House of Commons, but MPs voted, by a large majority, not to hear the petitioners. At the Convention, there was talk of a general strike or "sacred month". In the West Riding of Yorkshire and in south Wales, anger went even deeper, and underground preparations for a rising were undoubtedly made.

Newport Rising[edit]

Several outbreaks of violence ensued, leading to arrests and trials. One of the leaders of the movement, John Frost, on trial for treason, claimed in his defence that he had toured his territory of industrial Wales urging people not to break the law, although he was himself guilty of using language that some might interpret as a call to arms. Dr William Price of Llantrisant—more of a maverick than a mainstream Chartist—described Frost as putting "a sword in my hand and a rope around my neck".[16] Hardly surprisingly, there are no surviving letters outlining plans for insurrection, but physical force Chartists had undoubtedly started organising. By early autumn men were being drilled and armed in south Wales, and also in the West Riding. Secret cells were set up, covert meetings were held in the Chartist Caves at Llangynidr and weapons were manufactured as the Chartists armed themselves. Behind closed doors and in pub back rooms, plans were drawn up for a mass protest.[citation needed]

On the night of 3–4 November 1839 Frost led several thousand marchers through South Wales to the Westgate Hotel, Newport, Monmouthshire, where there was a confrontation. It seems that Frost and other local leaders were expecting to seize the town and trigger a national uprising. The result of the Newport Rising was a disaster for Chartism. The hotel was occupied by armed soldiers. A brief, violent, and bloody battle ensued. Shots were fired by both sides, although most contemporaries agree that the soldiers holding the building had vastly superior firepower. The Chartists were forced to retreat in disarray: more than twenty were killed, at least another fifty wounded.[citation needed]

Testimonies exist from contemporaries, such as the Yorkshire Chartist Ben Wilson, that Newport was to have been the signal for a national uprising. Despite this significant setback the movement remained remarkably buoyant, and remained so until late 1842. Whilst the majority of Chartists, under the leadership of Feargus O'Connor, concentrated on petitioning for Frost, Williams and William Jones to be pardoned, significant minorities in Sheffield and Bradford planned their own risings in response. Samuel Holberry led an abortive rising in Sheffield on 12 January; and on 26 January Robert Peddie attempted similar action in Bradford. In both Sheffield and Bradford spies had kept magistrates aware of the conspirators' plans, and these attempted risings were easily quashed. Frost and two other Newport leaders, Jones and Williams, were transported. Holberry and Peddie received long prison sentences with hard labour; Holberry died in prison and became a Chartist martyr.[1]:135–8,152–7

1842[edit]

"1842 was the year in which more energy was hurled against the authorities than in any other of the 19th century".[3]:295 In early May 1842, a second petition, of over three million signatures, was submitted, and was yet again rejected by Parliament. The Northern Star commented on the rejection:

Three and half millions have quietly, orderly, soberly, peaceably but firmly asked of their rulers to do justice; and their rulers have turned a deaf ear to that protest. Three and a half millions of people have asked permission to detail their wrongs, and enforce their claims for RIGHT, and the 'House' has resolved they should not be heard! Three and a half millions of the slave-class have holden out the olive branch of peace to the enfranchised and privileged classes and sought for a firm and compact union, on the principle of EQUALITY BEFORE THE LAW; and the enfranchised and privileged have refused to enter into a treaty! The same class is to be a slave class still. The mark and brand of inferiority is not to be removed. The assumption of inferiority is still to be maintained. The people are not to be free.[15]:34

The depression of 1842 led to a wave of strikes, as workers responded to the wage cuts imposed by employers. Calls for the implementation of the Charter were soon included alongside demands for the restoration of wages to previous levels. Working people went on strike in 14 English and 8 Scottish counties, principally in the Midlands, Lancashire, Cheshire, Yorkshire, and the Strathclyde region of Scotland. Typically, strikers resolved to cease work until wages were increased "until the People's charter becomes the Law of the Land". How far these strikes were directly Chartist in inspiration "was then, as now, a subject of much controversy".[17] The Leeds Mercury headlined them "The Chartist Insurrection", but suspicion also hung over the Anti-Corn Law League that manufacturers among its members deliberately closed mills to stir-up unrest. At the time, these disputes were collectively known as the Plug Plot as, in many cases, protesters removed the plugs from steam boilers powering industry to prevent their use. Amongst historians writing in the 20th century, the term General Strike was increasingly used.[18][19] Some modern historians prefer the description "strike wave".[1][15] In contrast, Mick Jenkins in his The General Strike of 1842[18] offers a Marxist interpretation, showing the strikes as highly organized with sophisticated political intentions. Unrest began in the Potteries of Staffordshire in early August, spreading north to Cheshire and Lancashire (where at Manchester a meeting of the Chartist national executive endorsed the strikes on the 16th). The strikes had begun spreading in Scotland and West Yorkshire from the 13th. There were outbreaks of serious violence, including property destruction and the ambushing of police convoys, in the Potteries and the West Riding. Though the government deployed soldiers to suppress violence, it was the practical problems in sustaining an indefinite stoppage that ultimately defeated the strikers. The drift back to work began on 19 August. Only Lancashire and Cheshire were still strike-bound by September, the Manchester powerloom weavers being the last to return to work on 26 September.[1]:223

The state hit back. Several Chartist leaders were arrested, including O'Connor, George Julian Harney, and Thomas Cooper. During the late summer of 1842, hundreds were incarcerated; in the Pottery Riots alone, 116 men and women went to prison. A smaller number, but still amounting to many dozens – such as William Ellis, who was convicted on perjured evidence – were transported. One protester, Josiah Heapy (19 years old), was shot dead. However, the government's most ambitious prosecution, personally led by the Attorney General, of O'Connor and 57 others (including almost all Chartism's national executive) failed: none were convicted of the serious charges, and those found guilty of minor offences were never actually sentenced. Cooper alone of the national Chartist leadership was convicted (at a different trial), having spoken at strike meetings in the Potteries. He was to write a long poem in prison called "The Purgatory of Suicides."[20]

Mid-1840s[edit]

Despite this second set of arrests, Chartist activity continued. Beginning in 1843, O'Connor suggested that the land contained the solution to workers' problems. This idea evolved into the Chartist Co-operative Land Company, later called the National Land Company. Workers would buy shares in the company, and the company would use those funds to purchase estates that would be subdivided into 2, 3, and 4 acre (0.8, 1.2, and 1.6 hectare) lots. Between 1844 and 1848, five estates were purchased, subdivided, and built on, and then settled by lucky shareholders, who were chosen by lot. Unfortunately for O'Connor, in 1848 a Select Committee was appointed by Parliament to investigate the financial viability of the scheme, and it was ordered that it be shut down. Cottages built by the Chartist Land Company are still standing and inhabited today in Oxfordshire, Worcestershire, Gloucestershire[21] and on the outskirts of London. Rosedene, a Chartist cottage in Dodford, Worcestershire, is owned and maintained by the National Trust, and is open to visitors by appointment.[22]

Candidates embracing Chartism also stood on numerous occasions in general elections. There were concerted campaigns in the election of 1841 and election of 1847, when O'Connor was elected for Nottingham. O'Connor became the only Chartist to be elected an MP; it was a remarkable victory for the movement. More commonly, Chartist candidates participated in the open meetings, called hustings, that were the first stage of an election. They frequently won the show of hands at the hustings, but then withdrew from the poll to expose the deeply undemocratic nature of the electoral system. This is what Harney did in a widely reported challenge against Lord Palmerston in Tiverton, Devon, in 1847. The last Chartist challenge at a parliamentary poll took place at Ripon in 1859.[1]:178–83,279–86,339–40

1848 petition[edit]

With O'Connor elected an MP and Europe swept by revolution, it was hardly surprising that Chartism reemerged as a powerful force in 1848. On 10 April 1848, a new Chartist Convention organised a mass meeting on Kennington Common, which would form a procession to present a third petition to Parliament. The estimate of the number of attendees varies by source; O'Connor said 300,000, the government 15,000, The Observer 50,000. Historians say 150,000.[23]:129–42 The authorities were well aware that the Chartists had no intention of staging an uprising, but were still intent on a large-scale display of force to counter the challenge. 100,000 special constables were recruited to bolster the police force.[24] In any case, the meeting was peaceful. The military had threatened to intervene if working people made any attempt to cross the Thames, and the petition was delivered to Parliament by a small group of Chartist leaders. The Chartists declared that their petition was signed by 6 million people, but House of Commons clerks announced that it was 1.9 million. In truth, the clerks could not have done their work in the time allocated to them, but their figure was widely reported, along with some of the pseudonyms appended to the petition such as "Punch" and "Sibthorp" (an ultra-Tory MP), and Chartism's credibility was undermined.[citation needed]

After the defeat of April 1848, there was an increase rather than a decline in Chartist activity. In Bingley, Yorkshire, a group of "physical force" Chartists led by Isaac Ickeringill were involved in a huge fracas at the local magistrates' court and later were prosecuted for rescuing two of their compatriots from the police.[25] The high point of the Chartist threat to the establishment in 1848 came not on 10 April but in June, when there was widespread drilling and arming in the West Riding and the devising of plots in London.[23]:116–22[26] The banning of public meetings, and new legislation on sedition and treason (rushed through Parliament immediately after 10 April), drove a significant number of Chartists (including the black Londoner William Cuffay) to plan insurrection. Cuffay was transported, dying in Australia.[27]

O'Connor's egotism and vanity have been identified as causes in the failure of Chartism. This was a common theme in histories of the movement until the 1970s.[28] But since the 1980s, historians (notably Dorothy Thompson) have emphasised O'Connor's indispensable contribution to Chartism. Further, Thompson argues that the causes of the movement's decline are too complex to be blamed on one man.[3][29] Historians have recently shown interest in Chartism after 1848. The final National Convention—attended by only a handful—was held in 1858. Throughout the 1850s, there remained pockets of strong support for the Chartist cause in places such as the Black Country.[1]:312–47[30]

Ernest Charles Jones became a leading figure in the National Charter Association during its decline, together with George Julian Harney, and helped to give the movement a clearer socialist direction.[31] Jones and Harney knew Karl Marx[32] and Friedrich Engels[33] personally. Marx and Engels at the same time commented on the Chartist movement and Jones' work in their letters and articles.[34][35]

In Kennington, the Brandon Estate features a large mural by Tony Hollaway, commissioned by London County Council's Edward Hollamby in the early 1960s, commemorating the Chartists' meeting on 10 April 1848.[36]

Christianity[edit]

During this period, some Christian churches in Britain held "that it was 'wrong for a Christian to meddle in political matters ... All of the denominations were particularly careful to disavow any political affiliation and he who was the least concerned with the 'affairs of this world' was considered the most saintly and worthy of emulation."[37]:24 This was at odds with many Christian Chartists for whom Christianity was "above all practical, something that must be carried into every walk of life. Furthermore, there was no possibility of divorcing it from political science."[37]:26 William Hill, a Swedenborgian minister, wrote in the Northern Star: "We are commanded ... to love our neighbors as ourselves ... this command is universal in its application, whether as friend, Christian or citizen. A man may be devout as a Christian ... but if as a citizen he claims rights for himself he refuses to confer upon others, he fails to fulfill the precept of Christ".[37]:26 The conflicts between these two views led many like Joseph Barker to see Britain's churches as pointless. "I have no faith in church organisations," he explained. "I believe it my duty to be a man; to live and move in the world at large; to battle with evil wherever I see it, and to aim at the annihilation of all corrupt institutions and at the establishment of all good, and generous, and useful institutions in their places."[38] To further this idea, some Christian Chartist Churches were formed where Christianity and radical politics were combined and considered inseparable. More than 20 Chartist Churches existed in Scotland by 1841.[39] Pamphlets made the point and vast audiences came to hear lectures on the same themes by the likes of J. R. Stephens, who was highly influential in the movement. Political preachers thus came into prominence.[37]:27–8

Between late 1844 and November 1845, subscriptions were raised for the publication of a hymnal,[40] which was apparently printed as a 64-page pamphlet and distributed for a nominal fee, although no known copy is thought to remain. In 2011, a previously unknown and uncatalogued smaller pamphlet of 16 hymns was discovered in Todmorden Library in the North of England.[41] This is believed to be the only Chartist Hymnal in existence. Heavily influenced by dissenting Christians, the hymns are about social justice, "striking down evil doers", and blessing Chartist enterprises, rather than the conventional themes of crucifixion, heaven, and family. Some of the hymns protest the exploitation of child labour and slavery. One proclaims, "Men of wealth and men of power/ Like locusts all thy gifts devour". Two celebrate the martyrs of the movement. "Great God! Is this the Patriot's Doom?" was composed for the funeral of Samuel Holberry, the Sheffield Chartist leader, who died in prison in 1843, while another honours John Frost, Zephaniah Williams, and William Jones, the Chartist leaders transported to Tasmania in the aftermath of the Newport rising of 1839.

The Chartists were especially critical of the Church of England for unequal distribution of the state funds it received, resulting in some bishops and higher dignitaries having grossly larger incomes than other clergy. This state of affairs led some Chartists to question the very idea of a state-sponsored church, leading them to call for absolute separation of church and state.[37]:59

Facing severe persecution in 1839, Chartists took to attending services at churches they held in contempt to display their numerical strength and express their dissatisfaction. Often they forewarned the preacher and demanded that he preach from texts they believed supported their cause, such as 2 Thessalonians 3:10, 2 Timothy 2:6, Matthew 19:23[42] and James 5:1-6.[43] In response, the set-upon ministers often preached the need to focus on things spiritual and not material, and of meekness and obedience to authority, citing such passages as Romans 13:1–7 and 1 Peter 2:13–17.[37]:38

Legacy[edit]

Eventual reforms[edit]

Chartism did not directly generate any reforms. It was not until 1867 that urban working men were admitted to the franchise under the Reform Act 1867, and not until 1918 that full manhood suffrage was achieved. Slowly the other points of the People's Charter were granted: secret voting was introduced in 1872 and the payment of MPs in 1911.[44] Annual elections remain the only Chartist demand not to be implemented. Participation in the Chartist Movement filled some working men with self-confidence: they learned to speak publicly, to send their poems and other writings off for publication—to be able, in short, to confidently articulate the feelings of working people. Many former Chartists went on to become journalists, poets, ministers, and councillors.[45]

Political elites feared the Chartists in the 1830s and 1840s as a dangerous threat to national stability.[46] In the Chartist stronghold of Manchester, the movement undermined the political power of the old Tory-Anglican elite that had controlled civic affairs. But the reformers of Manchester were themselves factionalised.[47]

After 1848, as the movement faded, its demands appeared less threatening and were gradually enacted by other reformers.[48] Middle-class parliamentary Radicals continued to press for an extension of the franchise in such organisations as the National Parliamentary and Financial Reform Association and the Reform Union. By the late 1850s, the celebrated John Bright was agitating in the country for franchise reform. But working-class radicals had not gone away. The Reform League campaigned for manhood suffrage in the 1860s, and included former Chartists in its ranks. Historians have also regarded Chartism as a forerunner to the UK Labour Party.[49][50][51]

Colonies[edit]

Chartism was also an important influence in some British colonies. Some leaders were transported to Australia, where they spread their beliefs. In 1854, Chartist demands were put forward by the miners at the Eureka Stockade on the gold fields at Ballarat, Victoria, Australia. Within two years of the military suppression of the Eureka revolt, the first elections of the Victoria parliament were held, with near-universal male suffrage and by secret ballot.[52] It has also been argued that Chartist influence in Australia led to other reforms in the late 19th century and well into the 20th century, including women's suffrage, relatively short 3-year parliamentary terms, preferential voting, compulsory voting and single transferable vote proportional representation.[53]

In the African colonies after 1920, there were occasional appearances of a "colonial Chartism" that called for improved welfare, upgraded education, freedom of speech, and greater political representation for natives.[54]

Criticism[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2018) |

Thomas Carlyle criticised Chartism in his 1840 long pamphlet Chartism.[55] He recognised that it was contrary to laissez-faire and, as laissez-faire along with "No-government" were the pillars of democracy, that it implied the replacement of democracy by class-rule government, something Carlyle was happy with so long as it was by the upper class.[dubious ]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f Malcolm Chase, Chartism: A New History (Manchester UP, 2007)

- ^ Boyd Hilton, A Mad, Bad, and Dangerous People?: England 1783–1846 (2006) pp 612–21

- ^ a b c d Dorothy Thompson, The Chartists: Popular Politics in the Industrial Revolution (1984).

- ^ Minute Book of the London Working Men's Association. British Library 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ Williams, David (1939). John Frost: A study in Chartism. Cardiff: University of Wales Press Board. pp. 100, 104, 107.

- ^ Joan Allen and Owen R. Ashton, Papers for the People: A Study of the Chartist Press (2005).

- ^ Bob Breton, "Violence and the Radical Imagination", Victorian Periodicals Review, Spring 2011, 44#1 pp. 24–41.

- ^ Cris Yelland, "Speech and Writing in the Northern Star", Labour History Review, Spring 2000, 65#1 pp. 22–40.

- ^ Navickas, Katrina (2015). Protest and the Politics of Space and Place, 1789–1848.

- ^ Navickas, Katrina; Crymble, Adam (2017-03-20). "From Chartist Newspaper to Digital Map of Grass-roots Meetings, 1841–44: Documenting Workflows". The Journal of Victorian Culture. 22 (2): 232–247. doi:10.1080/13555502.2017.1301179.

- ^ Shijie Guan, "Chartism and the First Opium War", History Workshop (October 1987), Issue 24, pp. 17–31.

- ^ "The six points | chartist ancestors". chartist ancestors. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- ^ Rosanvallon, Pierre (2013-11-15). The Society of Equals. Harvard University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-674-72644-4.

- ^ Victorianweb.org Archived February 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved on 2008-02-07

- ^ a b c Charlton, John, The Chartists: The First National Workers' Movement (1997)

- ^ David Williams, John Frost: a study in Chartism (1969) p 193

- ^ Edward Royle, Chartism (1996), p. 30.

- ^ a b Jenkins, Mick (1980). The General Strike of 1842. London: Lawrence and Wishart. ISBN 978-0853155300.

- ^ F.C. Mather, "The General Strike of 1842", in John Stevenson R. Quinault (eds), Popular Protest and Public Order (1974).

- ^ Kuduk, Stephanie (1 June 2001). "Sedition, Chartism, and Epic Poetry in Thomas Cooper's The Purgatory of Suicides". Victorian Poetry. 39 (2): 165–186. doi:10.1353/vp.2001.0012.

- ^ "Welcome to Chartist Ancestors - chartist ancestors". chartist ancestors. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Rosedene". National Trust. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ a b David Goodway, London Chartism, 1838–1848 (1982).

- ^ Rapport, Michael (2005), Nineteenth Century Europe, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-333-65246-6

- ^ Chartists.net Archived 2008-10-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John Saville, 1848: The British State and the Chartist Movement (1987), pp. 130–99.

- ^ Keith A. P. Sandiford, A Black Studies Primer: Heroes and Heroines of the African Diaspora, Hansib Publications, 2008, p. 137.

- ^ See especially R.G. Gammage, History of the Chartist movement (1854); J.T. Ward, Chartism (1973).

- ^ See also James Epstein, Lion of Freedom: Feargus O'Connor and the Chartist Movement (1982); Malcolm Chase, Chartism: A New History (2007); Paul Pickering, Feargus O'Connor: A Political Life (2008).

- ^ Keith Flett, Chartism after 1848 (2006).

- ^ George Douglas Howard Cole: Ernest Jones, in: G. D. H. Cole: Chartist portraits, Macmillan, London 1941

- ^ There are 52 letters from Jones to Marx between 1851 and 1868 kept.

- ^ There are eight letters from Jones to Engels between 1852 and 1867 kept.

- ^ Marx-Engels-Werke, Berlin (DDR) 1960/61, vol. 8, 9, 10, 27.

- ^ Ingolf Neunübel: Zu einigen ausgewählten Fragen und Problemen der Zusammenarbeit von Marx und Engels mit dem Führer der revolutionären Chartisten, Ernest Jones, im Jahre 1854, in: Beiträge zur Marx-Engels-Forschung 22. 1987, pp. 208–217.

- ^ Pereira, Dawn (2015). "Henry Moore and the Welfare State". Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity. Tate Research Publication. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Harold Underwood Faulkner, Chartism and the churches: a study in democracy (1916)

- ^ David Hempton, Methodism and politics in British society, 1750–1850 (1984) p 213

- ^ Devine, T.M. (2000). The Scottish Nation 1700-2000. Penguin. p. 279. ISBN 9780140230048.

- ^ "Hymns and the Chartists revisited". richardjohnbr.blogspot.co.uk. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ Calderdale Libraries, Northgate (15 July 2009). "National Chartist Hymn Book: From Weaver to Web". Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ Edward Stanley, 1839, "A Sermon Preached in Norwich Cathedral, on Sunday, August 18th, 1839, by the Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of Norwich, before an assemblage of a body of mechanics termed Chartists"

- ^ Manchester and Salford Advertiser, 17/8/1839

- ^ Frequently Asked Questions, Parliament.UK

- ^ Emma Griffin, "The making of the Chartists: popular politics and working-class autobiography in early Victorian Britain," English Historical Review, 538, June 2014 in EHR

- ^ Robert Saunders, "Chartism from above: British elites and the interpretation of Chartism", Historical Research, (2008) 81#213 pp 463–484

- ^ Michael J. Turner, "Local Politics and the Nature of Chartism: The Case of Manchester", Northern History, (2008), 45#2 pp 323–345

- ^ Margot C. Finn, After Chartism: Class and Nation in English Radical Politics 1848–1874 (2004)

- ^ Gabriel Tortella (2010). The Origins of the Twenty First Century. p. 88.

- ^ Giles Fraser (2012-10-05). "Before we decide to write off the Occupy movement, let's consider the legacy of the Chartists". The Guardian.

- ^ "BBC - KS3 Bitesize History = The Chartists: Revision". BBC.

- ^ Geoffrey Serle, The Golden Age: A History of the Colony of Victoria (1963) ch 9

- ^ Brett, Judith (2019). From Secret Ballot to Democracy Sausage: How Australia Got Compulsory Voting. Text Publishing Co. ISBN 9781925603842.

- ^ Barbara Bush, Imperialism, race, and resistance: Africa and Britain, 1919–1945 (1999) p. 261

- ^ Carlyle, Thomas. "Chartism". Retrieved 27 April 2018 – via Wikisource.

Further reading[edit]

- Ashton, Owen, Fyson, Robert, and Roberts, Stephen, The Chartist Legacy (1999) ESSAYS

- Briggs, Asa, 'Chartist Studies' (1959)

- Brown, Richard, Chartism (1998)

- Carver, Stephen, Shark Alley: The Memoirs of a Penny-a-Liner (2016), creative non-fiction account of the life of a Chartist journalist.

- Chase, Malcolm. Chartism: A New History (Manchester University Press, 2007), A standard scholarly history of the entire movement

- Chase, Malcolm. "'Labour's Candidates': Chartist Challenges at the Parliamentary Polls, 1839–1860." Labour History Review (Maney Publishing) 74, no. 1 (April 2009): 64-89.

- Epstein, James and Thompson, Dorothy, The Chartist Experience (1982) ESSAYS

- Fraser, W. Hamish, Chartism in Scotland (2010)

- Gammage, R. G. History of the Chartist Movement 1837-1854

- Hall, Robert, Voices of the People: Democracy and Chartist Political Identity (The Merlin Press, 2007) stresses the importance of regional loyalties and associations.

- Jones, David J. V., Chartism and the Chartists (1975).

- Jones, David J., The Last Rising; The Newport Insurrection 1839 (1985)

- O'Brien, Mark, "Perish the Privileged Orders": A Socialist history of the Chartist movement (1995)

- Pickering, Paul, Chartism and the Chartists in Manchester and Salford (1995)

- Roberts, Stephen, Radical Politicians and Poets in Early Victorian Britain: The Voices of Six Chartist Leaders (1993)

- Roberts, Stephen and Thompson, Dorothy, 'Images of Chartism' (1998) Contemporary illustrations

- Roberts, Stephen, 'The People's Charter: Democratic Agitation in Early Victorian Britain' (2003) ESSAYS

- Roberts, Stephen, The Chartist Prisoners: The Radical Lives of Thomas Cooper and Arthur O'Neill (2008)

- Schwarzkopf, Jutta, Women in the Chartist Movement (1991)

- Taylor, Miles, Ernest Jones, Chartism and the Romance of Politics (2003)

- Thompson, Dorothy. The Dignity of Chartism (Verso Books, 2015), Essays by a leading specialists.

Historiography[edit]

- Claeys, Gregory. "The Triumph of Class-Conscious Reformism in British Radicalism, 1790–1860" Historical Journal (1983) 26#4 pp. 969–985 in JSTOR

- Griffin, Emma, "The making of the Chartists: popular politics and working-class autobiography in early Victorian Britain," English Historical Review, 538, June 2014 in EHR

- Saunders, Robert. "Chartism from Above: British Elites and the Interpretation of Chartism", Historical Research 81:213 (August 2008): 463-484 (DOI).

- Taylor, Miles. "Rethinking the chartists: Searching for synthesis in the historiography of chartism", Historical Journal, (1996), 39#2 pp 479–95 in JSTOR

Primary sources[edit]

- The Chartist Movement in Britain, ed. Gregory Claeys (6 vols, Pickering and Chatto, 2001)

- §, Thomas, ed. (1880). Forty Years' Recollections: Literary and Political, Samson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington

- Mather, Frederick C. ed. (1980) Chartism and society: an anthology of documents 319pp

- Scheckner, Peter, ed. (1989). An Anthology of Chartist Poetry. Poetry of the British Working Class, 1830s–1850s, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, ISBN 0-8386-3345-5 (online preview)

- Kovalev, Yu. V. ed. (1956). "Antologiya Chartistskoy Literatury" [Anthology of Chartist Literature], Izd. Lit. na Inostr. Yazykakh, Moscow, 413 pp. (Russian introduction, with original Chartist texts in English).

External links[edit]

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Chartism |

Resources[edit]

- Chartist Ancestors

- The People's Charter

- British Library page including an image of the original charter

- Punch Series on "Great Chartist Demonstrations"

- Spartacus index on Chartism

- Victorian Web – The Chartists

- Ursula Stange: Annotated Bibliography on Chartism

No comments:

Post a Comment